The restoration of the Fishwick house was a two-phase process. Initially the concentration was on stabilising the building, repairing its necessary services and making it a comfortable home for the owners’ young family. This work continued for more than a decade. The second phase was a major restoration project supervised by a heritage architect which lasted over two years and incorporated the house’s landscaping and the regeneration of surrounding bushland. This section describes the most important projects in both restoration phases.

Heritage protocols require that significant work on a listed building should be well documented for the benefit of future generations. Also, in this regard, that contemporary works should be distinguishable from the original. Accordingly, while the material in this section is of a general nature, a very detailed description of the main restoration projects undertaken is on .pdf Details of Restoration.

Despite its run-down condition when bought by the present owners in the 1970s, the house was a very good subject for restoration. As well as being on a well-sited block with its curtilage generally well preserved and sympathetic, its fabric appeared to be mostly sound. Also, unlike most other Griffin houses in Castlecrag, previous residents had made no irreversible structural changes. Further, many critical design elements and fixtures which could have been broken or removed during the previous half-century had survived remarkably well; for example, almost all of the house’s original solid brass hardware, ceramic tiles, coloured glass, decorative timberwork and masonry detailing remained intact.

Initially, with the help of an architect friend and, through him, an excellent team of tradesmen, work began to stabilise its structure, to solve some serious technical problems, particularly with dangerously failing insulation on electrical cabling, and to stop rainwater penetration. During this early phase a great deal was learned about how the house functioned, information which was most valuable during the subsequent major restoration.

|

Peeling away various coverings on the main staircase revealed a small hole... |

|

...which proved to be the only visible evidence of the failure of its supporting structure. A re-build was mandatory. |

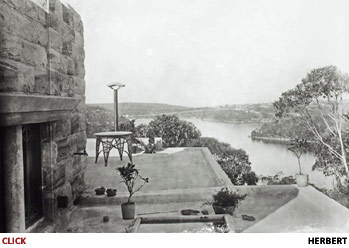

In the mid 1990s, water damage to the house’s much-photographed stone fireplace suddenly appeared. This proved to be caused by the failure of stormwater drainage pipes concealed within it. This near-catastrophic event sparked the decision to restore the entire house. Tropman & Tropman, a well-qualified and highly experienced heritage architectural firm, was commissioned to supervise the project. Its scope was wide and included extensive structural work, modernisation of services and replication of the house’s interior decorative finishes and detailing. The project ultimately encompassed the house's four outdoor recreation areas, the landscaping of its entire garden which dropped through five terrace levels and the restoration of several contiguous Griffin-designed reserves.

The exterior work was important because central to Griffin’s principles was that a building should be integrated with and have great respect for its landscape. Therefore, a necessary part of the process was the creation of native gardens and regeneration of the natural bushland on the property and its adjacent reserves. Again, this section describes the exterior work in general terms; for specifics open .pdf Details of Landscaping.

Such a wide-ranging programme required that many difficult decisions had to be made. Some were unexpected and urgent, being required to solve problems which arose as the work progressed. Typically these involved trade-offs between the need to ensure the utility of a solution while preserving high standards of authenticity and aesthetics, as well as being mindful of costs. For examples of such tradeoffs and their rationale open .pdf On Restoring a "Work of Art”.

This extensive work on the house was not only technically necessary but also proved to be a defining event in its history. Its careful restoration allowed Griffin’s principles and ideas, as well as his creative powers, to be clearly manifest. Thereafter, the house received much more attention from architecture and design professionals, heritage bodies and the general media, especially those interested in spreading the Griffin story more widely. Because of its unusual and striking appearance, many commissioned professional photographers to provide images for their records and descriptive material. This accounts for the exceptionally wide variety of high quality pictures which can be seen in the Images of House section.

Structure & Fabric

The most essential and important projects during the initial restoration phase which commenced in the mid-1970s were the stabilisation of the building’s structure and correction of many functional problems. There was a pressing need to overcome serious, sometimes critical failures in waterproofing and the house’s power, lighting, water, sewerage and gas services. For example, sewer lines which ran under the lounge room floor frequently became blocked by root penetration. This required the owners to become adroit users of hired "drain snake" machines lowered through a trapdoor in the flooring. Equally annoying, multiple leaks from heavy rains caused many electrical short circuits in poorly insulated cables and forced the acquisition of a large collection of buckets and old beach towels.

| Some problems were very serious. For example, a small crack in the mortar on a wall of the lounge began to widen rapidly with nearby rendering falling away. Clearly, the worsening crack indicated that a section of the house’s foundations was collapsing. The crack was directly above the north-east corner of the house where the foundation of the exterior wall rested not on the main sandstone platform but rather some two metres below on the next terrace level. Underpinning specialists were called-in. They excavated this foundation and discovered that, while Griffin's builder obviously thought he had found a solid sandstone footing at the lower level, in fact the foundation rested on a large, buried “floating” rock. Much deeper excavations were needed to find bedrock and safely underpin this corner of the house. |

Substantial damage to the lounge's walls was caused by its foundations being bedded on a “floating” rock. Correcting this required extensive underpinning and restoration work. |

|

Other structural problems such as spalling or “concrete cancer” in the roofing slabs and cracked internal walls were also clearly apparent. Most of the internal ceilings were actually the undersides of the house’s reinforced concrete roofing slabs. In many of these the expansive effect of corroding steel rods was clear from their sagging, deeply cracked surfaces. Specialised repairers worked on many such sites in the house.

|

Water penetration through cracks in ceiling slabs caused steel reinforcing rods to rust, generating extensive spalling. This was accelerated through usage of pre-moulded, weight reducing coke breeze inserts.

|

| It was often very difficult to find and then fix roof leaks. Griffin claimed that curing concrete roofing slabs under water would permanently seal them; it did not. [1] Evidently in search of a low-cost solution, a previous resident had covered the slabs with a simple tar-based membrane. This also failed over time as it became brittle and cracked extensively. Rain water then found its way into cracks in the slabs which, in turn, accelerated the corrosion of their steel reinforcing rods, causing concrete spalling. It was necessary to find a roofing membrane system which could cope both with the temperature change-induced movements of the slabs and with the problem of adequately flashing them against rough, vertical stone walls. Successively, two quite different membrane systems were installed but both ultimately failed. With time, technical improvements yielded a much improved multi-layered system which was installed and remains effective. Open .pdf Details of Restoration for more specific information on roofing and leakage problems. |

|

Fixtures & Fittings

During the late 1970s, work on the house was mostly concentrated on stabilising its structure and upgrading its services. The major exception was the necessity to strip out and rebuild the kitchen because of its very poor condition. Its floorboards had become rotten because moisture from the sandstone bedrock had risen through the floor. Most of its cabinets were missing or broken, the rendered walls and ceilings were severely cracked and some concealed service lines were faulty. In rebuilding the room, great care was taken to follow Griffin’s basic design concepts. For example, his original house plans showed the detailed profiling of the original kitchen cabinets and doors; this was followed in the new work.

Aside from rebuilding the kitchen, replacing some chipped ceramic items in the bathrooms and other minor work, the house’s fixtures and fittings received little attention until the major restoration in the 1990s. The heritage architect who then planned and supervised the work stressed that the authenticity of the project would largely rest on the care involved in restoring or replacing prominent internal items such as wall and light fittings, decorative features and furnishings.

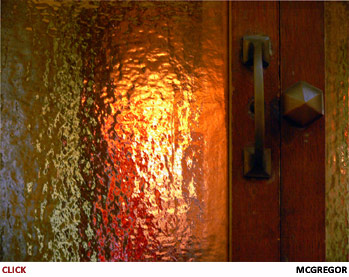

Most Griffin houses had their original layouts altered to gain more space. Also, they had generally been stripped of such things as their original kitchen and bathroom fittings, ceramic tiles, door and window hardware and internal glass and timber joinery. In the Fishwick house these had survived remarkably intact, albeit mostly covered with many layers of oil paint. For example, almost all the house’s glass doors still had their original coloured panes of glass and virtually all the brass door and window knobs, latches and handles had survived. Miraculously, some highly fragile items had survived over 65 years of use; for example, both of the house's bathrooms retained their original ceramic shower-heads and these remain attractive and highly functional.

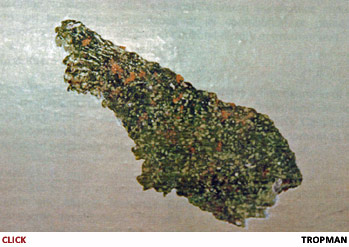

| There were some very fortunate outcomes to seemingly intractable problems. For example, in order to replace rusty galvanised iron water pipes embedded in the walls of the bathrooms, many of the original ceramic wall tiles needed to be removed; some were broken in the process. These were irreplaceable, being of very distinctive shape, texture and colour. Green tiles were needed in the ensuite bathroom, yellow in the second bathroom. The workmen were extremely lucky. They found replacement green tiles in the abandoned dining room ceiling fish pools and yellow tiles behind a 1950s kitchen cupboard which was being scrapped. |

The only known picture showing the dining room ceiling's fish pools which were replaced by skylights in the early 1930s. These were the source of irreplaceable green tiles required for a bathroom. |

| Other significant projects included rebuilding many rotted windows and most of the external doors. This task required fabricating and installing 168 Y-shaped wooden glazing bars of different sizes which were missing from all the upstairs windows and doors but visible in Griffin's plans and a number of old photographs. For descriptions of the most important work undertaken to repair or replace fixtures and fittings, open .pdf Details of Restoration. |

|

|

|

Finishes & Decoration

One of the most striking features of the Fishwick house is Griffin’s manipulation of colour, light, texture and space to create compelling and unexpected atmospheric effects. For this reason, the careful recreation of the house’s surface finishes and decoration was a very important part of the major restoration.

While Griffin was very much a man of his time, a believer in fresh thinking rather than nodding to the past and an avid user of modern materials and methods, he did not follow the then-emerging “Modernist” notion of form following function. In fact he incorporated many decorative elements, some flamboyant, in all his houses. He argued that it is essential to “include romance into our physical surroundings”. [2] Since the Fishwick house was emerging as a showpiece for Griffin’s design skills it was essential to strive to replicate the atmosphere he sought to create.

While it was important to return the surface colourings and wall textures as closely as possible to those originally used, good heritage conservation principles required that recreated finishes should remain distinguishable from the originals. [3] In this, the wide experience and advice of the heritage architect was most valuable because many value judgements needed to be made.

Griffin had created the complex textures on the lower sections of rendered walls by mixing multi-coloured pigments in the mortar before it was roughly applied. A means had to be found to generate similar textural effects on surfaces already smoothed by many layers of oil paints. Good results were obtained by applying opaque, deeply-toned base coats which were initially sponged with lighter coloured translucent glazes and then partially sponged with more heavily pigmented surface finishes. This produced a mottled, textured appearance, despite the under-surface actually being smooth.

When the restoration was complete, all of the internal surfaces of the building had been restored or refinished. Every effort was made to ensure that a visitor entering the house could sense how it might have presented itself in the late 1920s; creating the appropriate atmosphere was very important. To a great degree, it is the novelty, consistency and authenticity of the house’s decoration which has attracted much attention. For more on the restoration of the house’s finishes and decoration including a room-by-room description of the work involved open .pdf Details of Restoration.

Services

In most houses, service cables and pipes for electricity, telephone, water, sewerage, gas, drainage and the like are fed through specifically designed spaces behind wall surfaces, under floors or above ceilings. However, the Fishwick house has mostly solid sandstone walls, reinforced concrete slab ceilings and floors without cavities below them. [5] Repair or replacement of faulty service feeds is therefore very difficult.

Provision of hot water to the kitchen was an extreme example of re-routing a service line. The original galvanised iron pipe presumably failed and was replaced by a copper pipe which ran from the storage tank in the garage, through the house’s northern wall, up to roof level and then south across the entire roof span. It then dropped to ground level where, by a circuitous route, it entered the kitchen. This was an external hot water pipe run of over 20 metres (65ft). Some seven litres (15 pts) of cold water needed to be drained into the sink before the kitchen tap ran hot.

Another service line problem arose from Griffin’s design concept that there should be no visible guttering or downpipes on the house’s exterior. Sewerage and drainage from the upper floor were run inside the fabric of the building down mild steel pipes to ground level. There they joined terracotta drainage pipes under the floorboards of the entrance hall and lounge before leaving the house. The failure of a stormwater downpipe concealed within the lounge’s stone fireplace, which is possibly the most photographed structure in the building, caused severe damage. In fact, the urgent need to solve this specific problem reinforced the decision to begin the house’s major restoration.

Problems such as these were often difficult to solve, especially given the need to preserve the heritage qualities of the building. Much time, expense and resourcefulness were required to find acceptable solutions. Sometimes specialised technicians were employed to use such techniques as television probes, in-situ drain relining, embedding cables in the mortar tuck-pointing between sandstone blocks or using very long diamond drills to carry pipes through solid stone or masonry. [6]

Contemporary services made possible in similar ways throughout the house include multiple power and telephone outlets, ducted central heating, data and audio-visual cables connecting electronic devices throughout the house, satellite television, centrally-controlled security, exterior lighting and a programmable garden irrigation system. Importantly, in all these cases the necessary hardware was able to be concealed from view, thus preserving the house’s authenticity. For more information on service problems and their correction open .pdf Details of Restoration.

Landscaping

When the current owners bought the Fishwick house in 1976 its only garden was on the relatively flat terrace level below the picture window of the lounge. This had a lawn edged with garden beds containing exotic shrubs and flowers. The lower third of the property was literally impenetrable, being infested by bamboo and noxious weeds. [7] They had no access to or knowledge of the three terrace levels below or the contiguous Buttress Reserve. This uncontrolled "Terra Nullius" at the rear of the block was tolerated because of the many more urgent projects concerning the stability and functionality of the house itself.

| In the early 1990s, when the owners were temporarily living overseas, the local council introduced a mandatory bamboo eradication programme. In their absence, abortive attempts were made by inexpert contractors to remove the bamboo and its matted rhizomes by raising them in large clumps using a block and tackle hanging from the site’s large Port Jackson fig tree. Catastrophically, this slap-dash approach not only failed to eradicate the bamboo, it destroyed many of the house’s original dry stone garden walls which had previously been hidden from view by the bamboo. However, this action proved to provide some side benefits. As well as uncovering an eyesore (a large concrete sewerage pit which was soon removed) it also exposed for the first time in decades some skilfully constructed walled terracing, many wonderful rock formations, a small cave and, astoundingly, a set of sandstone steps still in reasonable condition which opened easy access to the two lowest terrace levels. |

...however the bamboo’s stumps and matted rhizomes remained. |

On their return from overseas, the owners began a much more disciplined bamboo and weed eradication effort as part of the major restoration of the house and its grounds. Because of bamboo’s capacity to spread its rhizomes very broadly, in order to be effective this work had to be extended into the Buttress Reserve and the neighbouring properties. This massive effort requiring hard manual labour took three years to complete but it also cleared the entire area of weeds, leaving only large native trees and shrubs. This ultimately proved to be excellent preparation for later bush regeneration work and encouraged the natural re-growth of native plants.

|

After the massive task of mattocking out the bamboo rhizomes, masons built a stone path which entirely encircled the large rear section of the block. |

The bamboo clearance uncovered a previously unknown set of stone steps beneath a sheer rocky outcrop. |

|

Weed control after initial manual eradication required laying a cover of mulch on all the lower terrace levels and neighbouring reserves. |

Aiming to surround the house with sympathetically planned landscaping using native plants, the owners enlisted the services of a specialist garden designer. To develop and maintain the new plantings they also contracted an expert with many clients in Castlecrag who specialised in planting and maintaining local indigenous trees, shrubs and grasses. Thus, the restoration of the house and the construction and regeneration of its garden and the nearby reserves were able to be approached and developed as a unified, harmonious project.

A team of stonemasons built new retaining walls using well-aged sandstone blocks from house demolitions. As well, they rebuilt the badly disturbed dry stone walls, mostly using sandstone rocks uncovered on the property. A delightful garden pond and waterfall were also created directly below the lounge’s picture window. Excavations on the block's lower levels had exposed a number of large boulders with deeply eroded faces worn into extraordinary patterns, so these were integrated into the layout of the pond. [8] Other major stonework projects were building an elevated garden and small ornamental pool in the front courtyard, restoring the sandstone steps to the maid’s quarters and designing and constructing the flagstone path which now meanders through and encircles the entire rear of the block, allowing easy access to the lower three terrace levels and to the Buttress Reserve.

|

Excavation of topsoil from garden beds revealed intriguingly-shaped natural sandstone boulders and rock formations. The garden pond was designed and built to incorporate them. |

|

Stonemasons found several large rocks on the block to complete the pond’s perimeter. A recycling system was installed to feed its small waterfall. |

So large was the area restored and so thorough were the weed eradication, rebuilding, planting and bush regeneration efforts that some three years passed before the native garden was completed. Existing fussy garden beds and exotic flowers, bushes and trees had been replaced by Australian native plants in natural, rugged bushland settings. The plants chosen were more formal very near the house but on the lower terraces they progressively blended more with the flora of the native bush, so that the house, its gardens and the neighbouring Buttress Reserve were wholly integrated as Griffin intended. [9] For more on the house's landscape designs, planting concepts and bush regeneration open .pdf Details of Landscaping.

Footnotes in this Section

1. For more on the construction and waterproofing of the ceiling slabs see the Top Roofs section in Architecture & Design.

2. The Writings of Walter Burley Griffin Dustin Griffin Ed. 2008 pp266-267

3. The Burra Charter defines the basic principles and procedures to be followed in the conservation of heritage properties. Following reconstruction and restoration any new work has to be distinguishable from the original work.

4. The Writings of Walter Burley Griffin ibid pp267-268

5. This was due to Griffin’s technique of infilling immediately under the floorboards to resist rot and repel termites. For details of this see Technology in the Architecture & Design section.

6. Accurate notes and sketches were made on all re-routing to assist future owners. A notebook containing these has 15 sections covering details of the house’s various systems and service layouts. The notebook has some 45 pages and almost 70 diagrams.

7. The bamboo barrier below the second terrace level was so tall and thick that their children enjoyed climbing into the upper limbs of the nearby Port Jackson fig tree and sliding down the bamboo to the ground below.

8. Hidden pipes and a pump circulate the water from the pond to the waterfall above.

9. For more information on the garden see Australian Gardens for a Changing Climate Burns 2008. pp48-53 and Garden Voices Latreille 2013. pp58-59, 66